From Bustling Cities to Farm Life: The Flock House Story

By Russell Poole

The Flock House story, like much else in Aotearoa, starts with wool. In the early decades of the colony sheep farmers ran huge estates in the back country, producing vast amounts of wool. During the First World War this wool was required in massive quantities in Great Britain. The merchant shipping that transported the wool was vulnerable to enemy submarines and so too were the Navy ships that protected them. Tens of thousands of sailors perished or incurred permanent injuries in the cause of defending New Zealand exported commodities.

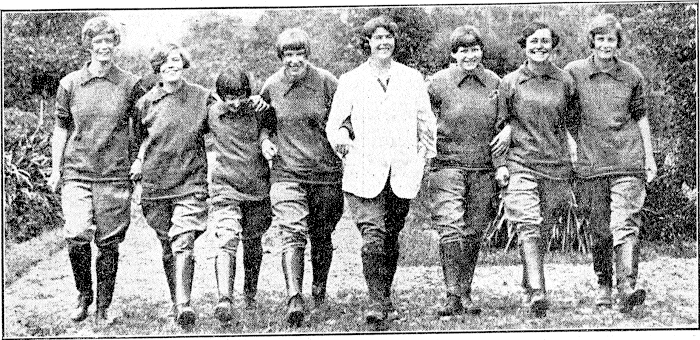

After the war the sheep farmers of New Zealand, led by Edward Newman, a farmer and MP living near Bulls, resolved to express their gratitude by helping the widows and children of these sailors. One way the farmers could help them while also helping themselves was to bring some of the teenaged children to this country and put them through a farm cadet course. These young people, as well as gaining a livelihood, would then form a supply of labour for the farmers. The boys were accommodated at Flock House, a stately homestead near Bulls, and the girls at an equally grand house called Shalimar in Awapuni, now a suburb of Palmerston North. For these young people the transition from the bustling port cities of Great Britain to a country town like Palmerston North or Bulls must have seemed extraordinary. Altogether, almost 800 trainees were brought out, 128 of them girls.

The course of training covered almost every imaginable aspect of farming, far too much to master in the prescribed six to eight months. As part of it the boys were set what can only be described as hard labour, planting thousands of trees in the sand dune country and grubbing out gorse on the main estate. Nevertheless, many of the trainees said they enjoyed the experience, no doubt buoyed up by the understanding that one day they might come into a farm of their own.

Following the basic training individual boys and girls worked an apprenticeship for three years with a farmer selected by the trustees of the Flock House scheme. Some trainees got lucky insofar as their employers treated them fairly, gave them further training in farming and helped them to socialise with other young people in the district. You hear of networks of these people in, for example, Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti who became lifelong friends or spouses.

Other trainees were not so lucky. Some led lonely lives on back-country farms, eating their meals on their own in the kitchen. Eric Leary ran away from an isolated farm near Harihari and somehow got himself to Ōtautahi (Christchurch), where he spent the rest of his life. Edna Preston (not her real name) was sexually harassed by her employer and sought help from her brother back in Scotland, who got her released from her apprenticeship by threatening to expose the Flock House placement system in the British press. The trustees only slowly came to the realisation that they needed to screen prospective employers more thoroughly.

How many trainees fulfilled their dreams and acquired a farm of their own? Only a few, it seems. Dorothy Hobbs married the owner of a large farm near Raetihi. Harry Saunders was balloted a farm near Pākaraka in the Whanganui district and ran cattle there for some years, though ultimately the property was too small to be economic. Roy Penellum worked variously as a farm labourer or farm manager. Harry and Leslie Hall moved to a country town after some years as farm labourers. Elsie Ring married and moved to Timaru. Allen Falconer got into the trucking business when the farm he was sharing with his brother at Panetapu, Waikato proved too small; he was briefly in the UK during the Second World War but opted to return to New Zealand, feeling that his native Scotland had offered him no prospects in his youth. George Hannah and Arthur Metcalf nearly starved as farm labourers during the Depression and returned to the United Kingdom as stowaways on the SS Coptic.

With such a variety of different life courses, it’s difficult to sum the Flock House scheme up. It seems, however, to represent a mix of well-meaning but perhaps rather naive benefactors and some definitely exploitative employers. Correspondingly, the descendants of the Flock House trainees testify to experiences that ranged all the way from success and prosperity to trauma and tragedy.

If you can add to this testimony, whether on the positive or the negative side, with stories of your ancestors’ experience of the Flock House scheme I would very much like to hear from you. If you would like to attend the Flock House commemoration in July this year you can find out more at https://flockhouse.nz/.

If you want to be notified of more stories like this, please subscribe to the Heritage newsletter here.